Seeing the wood and the trees

October 2024 marks the 100th anniversary of the forest herbarium and xylarium in Oxford. Professor Stephen Harris, Druce Curator of the Oxford University Herbaria, takes us on a tour through some of the history of these important collections: from colonial beginnings to the modern day’s deeply collaborative spirit.

Establishment of the collections

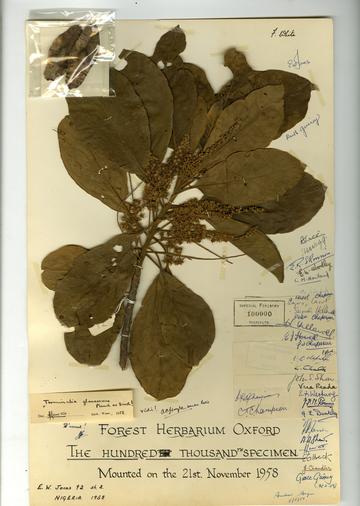

The 100,000th specimen added to the forest herbarium collection, of Terminalia glaucescens, mounted 21 November 1958

In 1924, the founding director of the Imperial Forestry Institute (IFI; later the Oxford Forestry Institute), Robert Troup, realised collections were fundamental to scientific forestry research and teaching. The IFI’s remit was to provide advanced training to forest officers in the then British colonies, and to function as a research centre for the ‘formation, tending, and protection of forests’. Troup believed facilities offered by the long-established botany herbarium (then at the Botanic Garden) were inadequate for research and teaching in forest systematics, tree identification, and the properties of wood. He therefore established a separate forest herbarium and xylarium (wood collection) in rooms rented from St John’s College. The forest herbarium only moved to its present location on South Parks Road – together with the botany herbarium – 27 years later, in 1951.

The first forest herbarium curator, Joseph Burtt Davy, stewarded what became a rapidly growing collection; by 1935 there were nearly 54,000 specimens – in November 1958, the 100,000th was added. Today, the forest herbarium, which is still growing – albeit more slowly – contains around 400,000 specimens. Soon after its foundation, the xylarium became the responsibility of Leonard Chalk; nearly 60% of the current wood collection, estimated at around 24,000 blocks, had been acquired by the time he retired in 1963.

For many years after their founding specimens came, unsurprisingly, from across the former empire. Contributed by Oxford-trained forestry officers, their accumulation and removal – under colonial practices of the period – looks very different to the way the herbaria are managed today, with not just the law of research but the spirit of it a drastically different picture.

Decades of forestry research

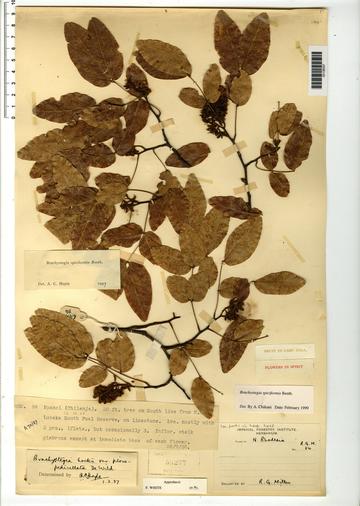

Herbarium specimen of Brachystegia spiciformis

The longevity of the collections reflects changing forestry research and teaching interests within the University and the wider world, as well as changing attitudes to how data are collected and science is done.

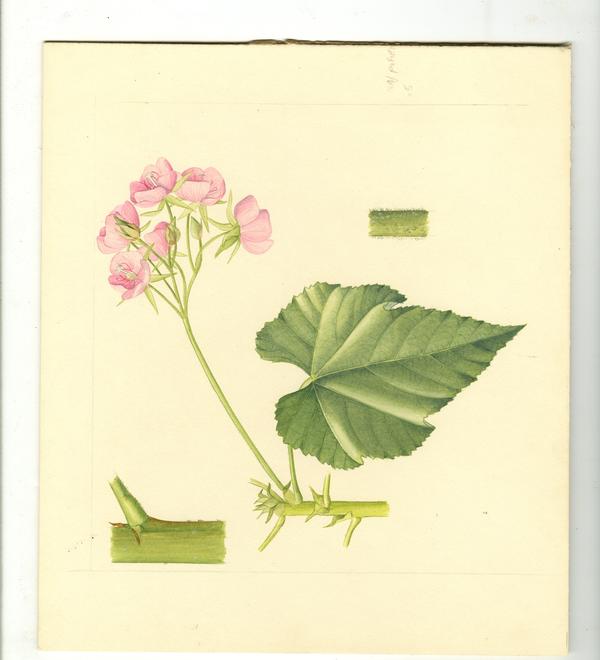

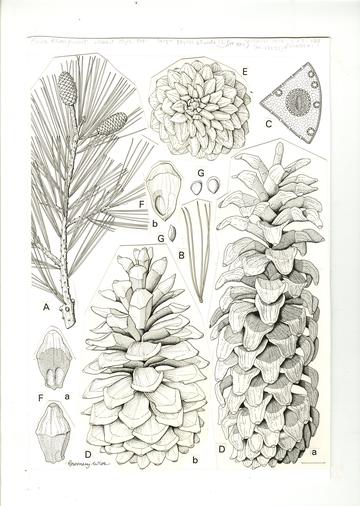

Arthur Hoyle joined the herbarium, and began a lifetime’s association with the legume genus Brachystegia, when identification of colonial timber resources was the priority for the collections. Brachystegia is one of the primary tree genera of miombo woodlands – a major tropical African ecosystem for plant and animal diversity and human-wildlife co-existence – but was poorly known by colonial foresters in the 1930s. When Hoyle died in the mid-1980s, his work remained incomplete, but was finally completed and published by Augustine Chikuni, a Malawian doctoral student, in the early twenty-first century. Other specific groups of trees also became associated with researchers in the Oxford forestry collections, including the ebony and mahogany families, neotropical pines and acacias in Africa. This research has benefited from the very fine botanical illustrators associated with the collections, including Maureen Griffiths, Janet Chandler, and, since the mid-1960s, Rosemary Wise.

For many historical reasons, particularly colonial links to the region, the forestry collections in Oxford are heavily focused on African trees, providing opportunities for researchers to understand species distributions and how species are integrated into vegetation types across the continent. In the 1980s, after decades of field experience, detailed knowledge of herbarium collections and collaborations across Europe and Africa, Frank White, a former herbarium curator, published a detailed map of African vegetation types and changed our understanding of broad-scale plant habitats across the continent.

From research to application

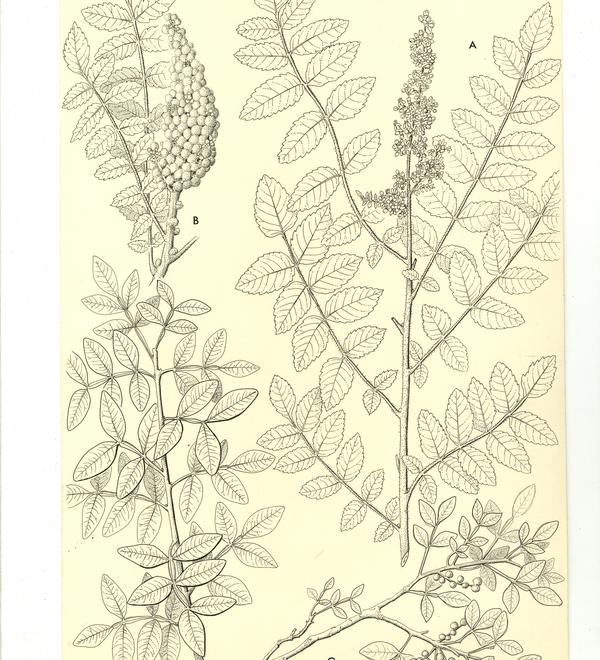

Line drawing illustration of Pinus strobiformis, by Rosemary Wise

The transfer of academic research to practical application has always been an important part of activity in the forest herbarium and xylarium. One of Burtt Davy’s early concerns had been to identify the specific willow species used to make cricket bats, and then determine how to maintain wood quality. Researchers working with the collections in the 1930s also recognised that linking local and scientific names with tree ecology was essential for the commercial timber harvesting in the forests of West and East Africa. Moreover, Chalk, along with Mary Margaret Chattaway and colleagues across several institutions, laid the foundations for modern investigations of wood anatomy and wood identification.

During the twentieth century, as the focus of national and international forestry shifted away from economic exploitation towards environmental change, plant diversity, and species conservation, the collections adapted. For example, William Hawthorne developed methods for rapid biodiversity assessment to assist forest policy in the 1990s, which together with several colleagues, including in Africa, enabled tropical areas of the continent rich in rare plants to be mapped.

From the 1960s, a forest genetics group in the Forestry Institute began to focus research on the evaluation, conservation, and improved use of forest trees in Africa and the Americas. By the 1990s, the quantity of data being used from botanical collections led to the genesis of the BRAHMS database, which today is used for managing natural history collections, botanic gardens, seed banks, field surveys, and taxonomic research worldwide.

Particularly over the past 30 years, the shift in focus has been paralleled by a shift in relationship with local researchers and communities. Over this period, access to material has been opened up and long-lasting, meaningful collaborations have been cultivated across the world.

Bringing our history with us

A century on, the University’s herbaria and xylarium are fully integrated – as the Oxford University Herbaria – in the Department of Biology. The next challenge is to move over 1.5 million objects into the new Life and Mind Building and find everything at the end of the process.

In the early days of the collections, access to them was restricted to select individuals. As complex as this move may be, it will make the collections more accessible than ever, including to the wider public, and gives us an opportunity to share more about these forgotten histories. It is essential that collections, which hold rich information for teaching and research, are actively used rather than being mere status symbols. We’re excited to have the opportunity to share these, while we look to the future and create a foundation for the next century of forest-based research and teaching in the University.